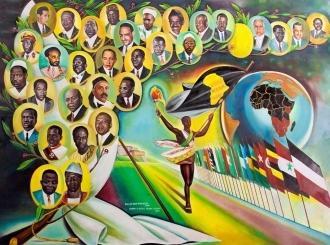

The celebration of fifty years of Pan-African institutional history is a time for reflection. Like the famous mythical Sankofa bird symbol, Africans must look into their past to create their future; acknowledging our previous mistakes and learning from them but also celebrating our successes and building on them.

This is aptly captured in the theme for this year’s celebration, ‘Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance’. A focus on African Renaissance gives an opportunity to reflect on Africa’s self-reliance trajectory and the need to demystify, appropriate and popularize our history, our shared values, and our narrative about the state of Africa today, in honor of the generations that went before us and to inspire current and future generations.

Pan-Africanism at its inception was more than just a search for racial or geographic identity. Initially led and popularized by Africans in the Diaspora such as Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. DuBois, it was a clear rejection of the laughable fallacy that Africans did not have a history. It was also a strong refutation of the mindset that defined Africa and Africans from the perspective of the historical experience of slavery, colonialism and racial discrimination. Rather it was the affirmation of the rich cultural heritage of African societies and the importance of achieving freedom and continental unity.

Since then the concept of Pan-Africanism has continued to evolve, measured by the challenges and aspirations of the African continent. During the independence period, this ideology enabled Africans to overcome domination and oppression by ending colonialism and apartheid in the continent. The possibility of rapid socio-economic transformation of the continent was another goal promoted from early days. As noted by Emperor Hailé Selassié during the launch of the OAU, “Unless the political liberty for which Africans have for long struggled is complemented and bolstered by a corresponding economic and social growth, the breath of life which sustains our freedom may flicker out.” This statement still rings true. [1]

Despite strong political mobilisation for the liberation from oppression, Africa has failed to fulfil its full potential. It is well known that in the early 1960s, at the time of the establishment of the OAU, there was high optimism that the continent will perform well. Several African countries were at par or had even higher GDP rates than their counterparts in Asia. It is now common place to mention that, the GDP per capita of Ghana and South Korea were at the same level in 1960. Up until 1975, the fastest growing developing country in the world was Gabon. Botswana’s growth rate exceeded that of Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Thailand. Despite the optimism of the time, Africa failed to complete the transformation journey which Asia has to a large degree now traversed. While East Asia’s share in world global exports grew from 2.25 % to 17.8% over a period of 40 years (1970 to 2010), Africa’s share in world global exports drastically reduced from 4.99% to the current 3.33%. This led to Africa being called the ‘hopeless continent’, ‘a scar on the conscience of humanity’ and many other Hegelian fallacies.

As we entered the 21st century, Pan-Africanism reflected Africa’s conscious need for not only political independence, regional integration and the improvements of its living standards, but also the throwing of the shackles of economic bondage and democratic stagnation that had seen it reverse the short lived prosperity of the independence era. This meant devising a new economic positioning and new forms of partnership in which Africa, as an equal partner, would negotiate with the rest of the world, with fierce defense of its own defined priorities. Without losing the key elements of unity, cultural heritage and freedom, the reinterpretation of Pan-Africanism in the form of an African Renaissance is very relevant. It is a new phase that requires popular participation and mobilization of the African people behind the goals of structural transformation and improved governance. Indeed, Africa’s Renaissance can only be complete when the African voice will be heard and taken into account.

The relevance of the Pan-Africanism ideal, and its continuous attraction to intellectuals both on the continent and in the Diaspora, will be measured by the ability to adjust to new demands and new generations. Indeed, the ability to continue to provide inspiration and conviction to Africans across ages is the trade mark of Pan-Africanism. Thankfully, things have changed for the better since the turn of the century. Six out of the ten fastest growing economies are in Africa, there is a marked reduction in the number and size of conflicts in the continent, democratic governance and the respect of human dignity are on the rise. Africa is therefore ripe for change. It must seize this moment for re-strategizing.

The AU’s proclaimed vision is for ‘an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena’. Laudable in its aspirations, what guarantees do we have that it will not remain rhetoric? We must ask ourselves how we reach these goals. A framework being jointly developed by the AU, AfDB and the ECA as part of the fifty years celebrations should identify the prerequisites for Africa’s sustained transformation in clear and unambiguous terms. Dubbed ‘vision 2063’, it should offer a reinterpretation of the continent’s trajectory and claim the 21st century as Africa’s!

What might draw Africa back from achieving its objectives?

In pursuing any bold transformation, there are a few risks that must be appreciated and tackled head on. Current challenges facing any developing countries are very different from past two decades. These include addressing borderless problems such as the impact of climate change, creating jobs while building an educated and innovative workforce, tackling the scourge of disease, famine and conflicts, as well as ensuring that Africa’s vast natural resource wealth benefits its people. Economic inequality, expanding opportunities for all, reducing illiteracy and creating the enabling conditions for the growth development and protection of nascent local industries are just a few examples of a myriad of tasks that will certainly continue to drag Africa down in the world scales.

Towards an African Renaissance.

One thing is sure; Africa must act very differently, if it is going to take advantage of the current momentum. African leaders need a paradigm shift in their thinking. This transformation has already begun and it shows itself in diverse ways. For example, the perceptible change in the orientation of current African leaders from a dependence on external aid and external actors to an Afro-centric and internal support system. Issa Diallo, one of my predecessors, in an interview he granted in 1993, questioned the rationale behind Africans expecting foreigners to build their countries for them[2]. An aid dependence mentality is slowly giving a space to a more assertive leadership.

Starting from the original OAU Charter, there already existed a myriad of resolutions, treaties, accords and inter-governmental agreements to sustain Africa’s ambitions. What is needed now is for African leaders to move their agenda forward. The advantages of regional integration were recognised by Africans through the Pan-African ideology long before others and even longer before the term ‘globalisation’ was coined. The OAU’s creation simply reflected this awareness. The benefits of regional cooperation - increased investment, sustainability, consolidation of economic and political reforms, increased global competitiveness, prevention of conflict- are accepted, but sometimes just that: accepted.

If Africa is going to own its narrative, it has to preserve its policy space and try out its own development approaches. Renaissance means ‘revival’ or ‘rebirth’ and in the context of its usage now, not only offers an opportunity to awaken the spirit of Africa in the 21st century, but also a rallying call to rid the continent of poverty, instability, corruption and neglect. This new mindset means the need to rethink the traditional models of growth and development. In conclusion, the spirit of African unity is alive. It still lives amongst Africans and this year’s celebrations are a unique opportunity to rethink, restrategise and replan. As Patrice Lumumba said so long ago, ‘The day will come when History will speak... Africa will write its own history… It will be a history of glory and dignity. Long live Africa!![3]

[1] ECA, AU. 2013. Celebrating success: Africa’s voice over 50 Years 1963-2013. Speech of Emperor Haile Selassie during the inauguration of the OAU in 1963

[2] Interview with Issa Diallo in ‘The Courier’ Jan 1992. http://collections.infocollections.org/ukedu/uk/d/Jec131e/1.1.html

[3] Patrice Lumumba, 1961. Letter from Thysville Prison to Mrs. Lumumba. http://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/lumumba/1961/xx/letter.htmBased on my interventions during the 50th anniversary of the OAU/AU in Addis Ababa, 24-25th May 2013